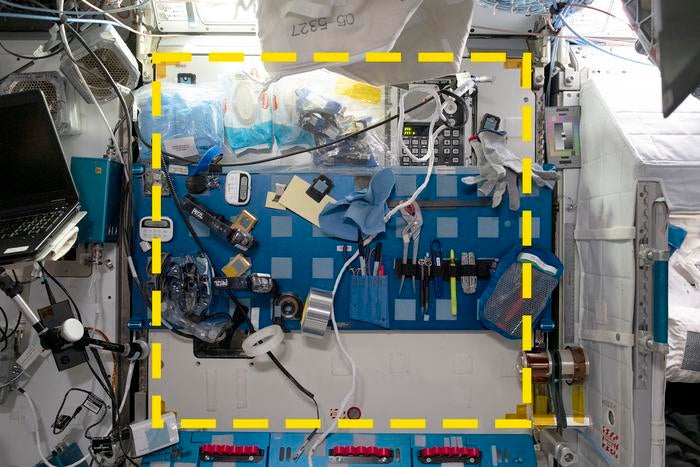

A sample site from the Sampling Quadrangle Assemblages Research Experiment (SQuARE), quadrat 03 in the starboard servicing area of the International Space Station. An open crew station is visible on the right. The yellow dotted line indicates the boundaries of the sample area. Image credit: NASA/ISSAP/Walsh et al., 2024, PLOS ONE, CC-BY 4.0

New results from the first archaeological fieldwork in space show that the International Space Station is a lush cultural landscape where the crew creates its own “gravity” to replace Earth’s and adapts the module spaces to suit their needs.

Archaeology is commonly thought of as the study of the distant past, but it is an excellent field for studying how humans adapt to long-term space flight.

In the SQuARE experiment, described in our new paper in PLOS ONE, we redesigned a standard method of archaeology for use in space and had it carried out by astronauts.

Archaeology … in … space!

The International Space Station is the first permanent human settlement in space. Almost 280 people have visited it in the last 23 years.

Our team studied exhibited photographs, religious symbols and artwork of crew members from different countries, observed cargo returned to Earth, and used NASA’s historical photo archive to examine relationships between crew members serving together.

We also looked at simple technologies like Velcro fasteners and resealable plastic bags that astronauts use to replicate the Earth’s effect of gravity in the microgravity environment – keeping things where you leave them rather than floating away.

Finally, we collected data on how the crew used objects inside the space station by adapting one of the most traditional archaeological techniques, the “shovel test pit.”

On the ground, once an archaeological site has been identified, a grid of one-meter squares is laid out and some of these are dug as “test pits.” These samples provide an impression of the site as a whole.

In January 2022, we asked the space station crew to identify five roughly square sample areas. We chose the square locations to include areas for work, science, exercise, and leisure. The crew also selected a sixth area based on their own ideas of what might be interesting to observe. Our study was sponsored by the International Space Station National Laboratory.

Then, every day for 60 days, the crew photographed each square to document the objects within its boundaries. Everything in space culture has an acronym, so we called this activity the Sampling Quadrangle Assemblages Research Experiment, or SQuARE.

The resulting photos show the richness of the space station’s cultural landscape and at the same time reveal how far life in space is from science fiction images.

The space station is crowded and chaotic, cramped and dirty. There are no boundaries between the work area and the crew’s rest area. Privacy is minimal or nonexistent. There isn’t even a shower.

What we saw on the squares

We can now present results from the analysis of the first two squares. One was located in the US module Node 2, where there are four crew sleeping quarters and connections to the European and Japanese laboratories. Visiting spacecraft often dock here. Our target was a wall where the Maintenance Work Area (MWA) is located. There is a blue metal plate with 40 Velcro squares and below it a table for attaching equipment or conducting experiments.

NASA intended the area to be used for maintenance, but we found little evidence of maintenance and little scientific activity there. In fact, for 50 of the 60 days we studied, the space was used solely for storage of items that may not even have been used there.

The amount of Velcro here made it a perfect place for ad hoc Storage. Almost half of all items recorded (44%) related to holding other items in place.

The other square we completed was in the US module Node 3, which houses exercise equipment and the toilet. It is also a passageway to the crew’s favorite part of the space station, the seven-sided cupola window, and to the storage modules.

This wall had no specific function and was therefore used for various purposes, such as storing a laptop, an antibacterial experiment and resealable bags. And during the 52 days of SQuARE, this was also the place where a crew member kept his toiletry kit.

It somehow makes sense to keep the toiletries near the toilet and exercise equipment that each astronaut uses for hours every day. But this is a very public space where others are constantly passing by. The placement of the toiletry kit shows how inadequate the facilities are in terms of hygiene and privacy.

What does this mean?

Our analysis of squares 03 and 05 helped us understand how restraints like Velcro create a kind of temporary gravity.

Shackles used to hold an object form an area of active gravity, while unused shackles represent potential gravity. Artifact analysis tells us how much potential gravity is present at each location.

The space station’s focus is on scientific work, and this requires astronauts to deploy a large number of objects. Field 03 shows how they transformed an area intended for maintenance work into a staging area for various objects on their journeys around the station.

Our data suggest that designers of future space stations—such as the commercial stations currently planned for low Earth orbit or the Gateway station being built for lunar orbit—may need to give storage a higher priority.

Square 05 shows how a publicly accessible wall area has been claimed by an unknown crew member for personal storage. We already know that privacy is not optimally protected, but the fact that the toiletry bag can still be found in this location shows how the crew redesigns the spaces to compensate for this.

What makes our conclusions so significant is that they are based on evidence. Analysis of the first two fields suggests that data from all six fields will provide further insights into humanity’s longest-standing space habitat.

Current plans call for the space station to be deorbited in 2031, so this experiment may be our only chance to collect archaeological data.

The authors thank our contributors Shawn Graham, Chantal Brousseau, and Salma Abdullah for their work.

![]()

Justin St. P. Walsh, Professor of Art History, Archaeology and Space Science, Chapman University and Alice Gorman, associate professor of archaeology and space studies, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.